Main Pioneer Menu | Profiles Index | Search Engine

Supplina Hamilton

Pioneer Washington Preacher

By Charles Dailey - Updated 2006

With assistance from Glen Hamilton of MyHamiltonFamily.org

At a Glance: Born: Illinois April 23, 1832 Emigrated: With the Powell Wagon Train in 1851 Settled: East of Albany, Oregon Baptized: 1852 Married: Sarah Jane Sumpter in 1858 Ordained: Walla Walla, 1867 Preached: Dixie, WA

Dayton, WA

Spring Valley, WA

Waitsburg, WADied: February 9, 1905 Buried: Pleasant Valley Cemetery

St. John, Whitman Co., Washingon

If Supplina Hamilton had a social problem, it was the spelling of his name. Take your pick: Supline, Sufflina, and even Samuel. When Freeman Walden reported on the work in Washington State to John T. Brown's Churches of Christ, he spoke of Samuel Hamilton. We are reasonably sure that this is Supplina Hamilton. There is no other reference to a Samuel Hamilton in Washington State. Some of this close friends solved the name problem by calling him "Doc."Young Hamilton was orphaned as a youth and lived with or near John Alkire Powell and his wife Savilla. John was a man of leadership as seen by his leading of the wagon train of family members to Oregon. Wagon train captains were elected by the other members of the train.

One writer said,

John had a powerful physique; he was six feet in height and weighed two hundred and twenty-five pounds. A man of indomitable will, he knew no task (to be) unsurmountable. He was a man of force and influence, highly esteemed by all who knew him.This John A. Powell was the role model for a developing Supplina. He was 19 when he signed on as a wagon driver for the trip to Oregon. John was a powerful preacher and made preaching desirable for the young man.His commanding appearance, his strong, clear voice and his logic and magnetism easily enabled him to hold the undivided attention of his audiences for an hour, and often much longer.

After the party arrived in Linn County, Supplina worked in John Powell's saw mill, cutting the lumber and keeping the dam that suppled the water power in good condition. It appears from the "Day Book" as John called it, that Supplina received $1.25 per day for his work when first hired. But then, 40 feet of one inch lumber sold for 80¢.

|

Photo Courtesy of Jeanne Welter |

Seven years after arriving, Supplina married Virginian Jane Sumpter and his mentor John Powell performed the ceremony. They held property in Linn County because they are listed in Volume 17 of Oregon Donation Land Claim Families. By the time of the 1860 census, Supplina is listed as a farmer with a net worth approaching that of John A. Powell. Glen Hamilton notes the census record shows a three-year-old named George Cox as a family member. It appears that the orphan lad Supplina has taken in an orphan child himself.

By 1863 the family is living in Umatilla County, Oregon just south of Walla Walla, Washington. A listing of the Umatilla County Officers for 1863 shows our man was one of two county commissioners that year. After the formation of Umatilla County from Wasco County in 1862, Supplina had been appointed as commissioner until the regular election in 1864.

In 1867 the family had moved north into Walla Walla County in Washington Territory. It was here he was ordained to preach by two elders of the "Walla Walla River" church, Ransom Wells and William H. Robbins. That year he ran for county commissioner on the Republican ticket, but was defeated. On the same ballot W. T. Barnes of the Dixie Church was running for commissioner as a Democrat.

By the time of the 1870 census, Supplina and Jane had moved south and were living in the Aumsville area, near Turner, Oregon. He was 38 and Jane was 32 and they list six children. His employment is listed as blacksmith. They remained there until at least 1872.

The are found at Waitsburg, Walla Walla County, Washington in 1875 and that same year homesteaded on land about seven miles from town. The family harvested wheat as well as growing melons and other fruits and vegetables. Supplina was known for his blacksmith work and even helped out the neighbors with medical advice.

In the 1880 census, he is listed as a preacher. This census also lists two grandchildren. Supplina was in the ranks of the preacher-farmers that worked hard at ministering, but did not receive pay for that work.

Much of his preaching career centered in Walla Walla County. In 1876, his name is connected with Spring Valley. In 1883, he is at Waitsburg. Two years later, he is resident at Dixie.

By 1890, the family is living in Whitman County, Washington, in the vicinity of St. John.

|

Photo Courtesy of Glen Hamilton |

Near the end of his earthly sojourn, Supplina looked back to the year he was 19, traveling the Oregon Trail. We have included the full text of his well-done letter, along with some graphics and comments.S. Hamilton -Glen Hamilton points out a tradition that began with Supplina:

Endicott, Washington, January 9, 1900.

Dr. J. M. Powell,

Spokane, Washington.Dear Sir:

After so long I will try to answer your letter of October 18, 1899, and will proceed with my story. I am now about sixty-eight years old; my memory has failed somewhat, my eyesight very much, and my hand is nervous, but I will do the best I can. Now to my story.The train that I was with was known as Powell's train. It consisted of John A. Powell, Noah Powell, Alfred Powell and George Alkire as the old men of the company. Then there were Wm. McFadden and F. S. Powell, young married men. The young men or larger boys of the train were A. Steuben Powell, J. B. Smith, John Alkire, Wm. Shirl, S. Hamilton and James Henry Powell, teamsters aged about eighteen to twenty years. The old men mentioned all had families. Jemima Powell and Ann Shirl were young women. There were also smaller boys and girls too numerous to mention.

(There is a profile of the Powell brothers.)The bachelor train, as I remember it, consisted of the following persons: Joseph Williams, John Davis, James Turner, J. M. Jacks, Jack Engle, Bob Brown, Press and Sam Black, and Bob Estle.The reasons for leaving Illinois to come West were various. The old men with families came to get cheap land for themselves and their children, as well as a milder climate, better health and better financial conditions. Others were attracted by the gold mines. As for myself, I was an orphan boy, and my home was anywhere that I was treated kindly. I wanted to see the elephants, so came West to grow up with the country.

We started from home in Menard County, Illinois, on the 3rd day of April 1851, reached Havana on the Illinois River April 4th in a snow squall, so laid over a half day, crossed on the fifth, and stopped that night at a farmhouse at the edge of a crab-apple thicket to buy corn, as everything had to be fed until at least the first of May. Here we met with our first misfortune. There had been a new road cut through the crab apple patch. Some sticks as large as a shovel handle had been cut off with a single blow of an axe so as to leave them about eighteen inches long, sloping and sharp at each end. One of Uncle John's fine mares stepped on the end of one of these sticks so as to throw the other end up, striking a large blood vessel inside of the thigh, bleeding her to death quickly.

I will here say that our outfits each consisted of a good stout wagon and four yokes, or eight head of oxen, except that the old men each had a family carriage drawn by two horses. We crossed the Mississippi River at Ft. Madison, Iowa, thence travelling westward striking the Mormon trail for Canesville on the Missouri River. After getting out a few miles from the Mississippi the country was but thinly settled. In fact all that we could see from our train was a Mormon family or two settled where there were creeks or springs and a little timber. They lived by hunting, raising corn and fodder to sell to emigrants, of which there seemed to be an abundance. I thought I had seen deer in the Sangamon River bottoms and on Salt Creek, Illinois, and so I had, but they were few compared to what we saw in the open and high prairies in central and western Iowa between the creeks and groves of timber. Of course we could not count them, but the old men estimate that there were as many as three hundred in a single band.

(These men brought their families in horse-drawn carriages. They are among the few.)I think of nothing of interest until we reached Canesville on high ground about one mile from the east bank of the Missouri River. About the 28th of April we moved about mile below town where there was wood, water, and a little grass, to lay over till grass got better on the plains. This was the last chance to get corn or other feed. Canesville was strictly a Mormon town, but the people were sociable and clever. They had plenty of corn and wild grass hay as well a provisions to sell us. They had everything to eat or drink produced in the Middle West, from corn whiskey to western reserved cheese. There was a large blacksmith shop where you could get anything in that line from a wagon tire to a ox-bow key, but it took money. They were there for that purpose. The town was built of logs, some round and some hewn, but all neat for their kind.

About the 10th or 12th of May we crossed the river, I think a little above where the city of Omaha now stands. An amusing incident occurred here. There had been a hog about a hundred pounds weight that had followed us for several days before reaching the Canesville camp. When we came to cross the Missouri River, the boat was very small so we swam the cattle. The hog was on hand and went into the river with them. Some trouble was experienced in getting the cattle to leave the shore, and while they were swimming around, a cow came into proper position so that the hog climbed on her back and rode across the river, sliding off as the cow went off the bank, and got out all right amid many cheer. We then gathered our teams and pulled around the point to the top of the hill or ridge where Omaha now stands. There we saw the first Indian camp, but the Indians were friendly.

I think of nothing more of special interest until we ha travelled probably a hundred miles up the Platte River. One morning shortly after starting out we saw a large herd of buffalo across the river, pursued by large white wolves trying to catch the calves. There was an island in the river a little way ahead, and the buffaloes crossed the first branch onto it. There we could see that the males had formed a ring with the cows and calves inside. They fought the wolves off for a while, but as we got about opposite the island, the buffaloes started again, coming for the center of the train, which then numbered about twenty teams. The captain ordered the rear part of the train to stop and try to hold the teams, while the front part moved on leaving as large a gap as possible. The train was broken at my lead cattle, where I stood and held to them until the entire herd of buffalo two or three hundred had passed. Some of them passed near enough that I could see the color of their eyes, though they were in full run, and were making the earth roar and tremble with their tread. Meanwhile, the wolves had stopped.

(To track mileage, at least one wagon was equipped with a "roadometer" on a back wheel so mileage numbers were precise. The device had a capacity for measuring up to 10 miles, so had to be reset at least once each day.

Passing up the Platte another hundred miles or so we came to a stream that emptied into the Platte, called Shell Creek. As I remember it, it was twelve or fourteen feet wide and about ten feet deep, and the banks were running full through a flat country. There was nothing left for us but to bridge the creek, which we did, using logs for stringers and poles for lumber. We got everything across that night, and camped on a little elevation on this side. It rained nearly all night, and the next morning we were surrounded by water at a short distance. We hitched up to go as the water was likely to be higher before long. But just then the captain ordered all teams taken loose from the wagons as there was a storm at hand, and the teamsters must hold their teams. Now hail of large size began to fall, and plenty of rain came with it. Each ox- driver had his near leader by the horn, and had to stem the storm and circle the oxen around to keep them going. Nearby there was a basin with water knee-deep in it at the start. J. Turner, one of the bachelors, whose team was hard to manage, was dragged into this lake, which was nearly waist-deep when the storm ceased. We then hitched up and drove till noon through water from ankle to hip deep, but camped on high ground that night. During the month of June rain and hail storms were an everyday occurrence.

One day I had a somewhat interesting and lonely experience with a large, dark-grey wolf. I went alone in the morning to look after some cattle when I found said wolf smelling around among them. I could only surmise his object as the cattle seemed to pay put little attention to him. I meditated a moment over what I would do with him, as he seemed to care but little for my presence. Being armed with only a hard wood stick about five feet long and three-fourths of an inch thick, I decided to scare him by exercising my lungs at him and at the same time wielding my stick. At that he began a retreat. I then thought to follow up my victory, but Mr. Wolf soon gave me to understand that while he was not aggressive he yet recognized the right of self-defense, by turning part-way around and showing me his teeth. I retreated in good order.

I think of nothing more of interest until we reached Ham's fork. We camped here on the 3rd of July. Here the bachelor part of our train laid over while we moved on. The train divided by mutual consent, thinking that both parts could make better time by travelling in small trains. We heard no more of them until they overtook us in Grande Ronde Valley, Oregon, where we learned that Press Black had been shot through the body by an Indian who was in hiding. They never saw an Indian anywhere near the place. They hauled Black swinging on a cot fastened to the wagon-bows for seventeen days, then laid him to rest. We parted there again, and I saw only John Davis, Jack Engle and Bob Estle thereafter.

I would here speak of Mrs. McFadden's death was it not that I presume that you have already learned more about that than I could tell. So I let it pass, except to say that she was buried at Lee's Encampment in the Blue Mountains. The place was later known as Meacham Station.

After leaving the Blue Mountains we came into the Umatilla Indian country where we found the Indians not only friendly but quite sociable as far as we could understand each other. Here we found the open bunch grass hills, as far as the eye could see, covered with hundreds and thousands of Indian horses of all colors and sizes from about eight hundred pounds downward, and all fat and fine, in striking contrast to ours which were little more then than skin and bones.

The next incident of interest occurred at the Deschutes River. We had to ferry our wagons one at a time owing to the smallness of the boat, and the rapids in the stream. Steuben Powell and myself were helping the ferrymen. When about the middle of the river, which was about five hundred feet across, the cable broke at the west bank and we started down the stream at a two-forty gait. However, we caught the guy-rope, and pulled the main line in, but had nothing to make it fast to. To the side of us some men in a boat, including two Indians, seized the cable and gradually checked the boat, swinging it slowly to the east bank. The excitement was allayed, which I think was greater on the bank than on the boat. We had to wait for the rope to be stretched across the river again, which was done with much difficulty.

A man came up on horseback, whose train had crossed ahead of us, who for some cause had fallen behind. He undertook to ford the river at the head of an island a little below the ferry. All hands were watching almost breathlessly with hope and fear. He crossed the first branch all right and appeared to us to be almost across the second when his horse struck swimming water. The current was strong and, of course, the horse was carried down. The rider became excited and tried to turn the horse upeam with the bridle, which resulted in pulling the horse over onto his side. Then a general scuffle began. I saw the horse turn over three times carrying the man with him each time. I saw them both go down, but we were on the opposite side of the river. Meanwhile the ferry-man had called some Indians who came running to the scene, throwing their clothes as they ran. They saw the man rise and sink the third time. They dove for him and brought him out, rolled him across a rock and brought him to. The horse was drowned but the Siwashes pulled him ashore and saved the man's rig for him. The pony was fat and the Indians had a feast.

We all got across that night and camped on the opposite bank. The next morning we started for Barlow's gate at the east foot of the Cascade Mountains. Here we saw much stuff that had been hauled nearly two thousand miles to be thrown away almost at the end of the journey. There was a cross-cut saw, a large cupboard, a cookstove, a grindstone, and other things too numerous to mention.

On August 29th we started into the mountains. About noon it began to rain, and continued to rain almost incessantly for four days. Nothing of interest occurred more than clearing logs out of the way until we reached Laurel Hill. We had to go down it, and as it was so steep that the ordinary lock would not hold the wagon, something else must be resorted to. Some cut small trees, trimmed the limbs six or eight inches long, and chained the top end to the hind axle. Others made rough locks by wrapping log chains several times around the tire and fastening the end to the wagon, so as to hold the hind wheels from turning. The road bed was worn down so as to form a channel for the water, which was running quite a creek. Then in the middle of a heavy rain we started down the hill, each wagon carrying with it a fair wagon load of loose rock to pile up at the foot of the hill. Here we unloaded logs and loosened wheels, and forded the Sandy River.

(See the Laurel Hill display on this link.)Then up a long slope to a high ridge known as the Devil's Back Bone, thence along said ridge to a steep clay point, not so long as Laurel Hill but very steep and slick. Here we unhitched the teams, made a cable of log chains as long as the hill and hitched the chain to the hind axle. Then we wrapped the chain around a tree and let it out by degrees with two men at the tongue. We got down the last hill worthy of note September 3, and reached Foster's Ranch, fourteen miles east of Oregon City, having been five months to a day from our starting point in Illinois. Here the journey ends.You speak of trouble with the Indians. I will say that while we heard of other trains having trouble with Indians from time to time, the Powell train proper had none whatever. I came with Uncle Noah. Uncle Al had a horse stolen near Ft. Hall, but that was evidently done by a white man.

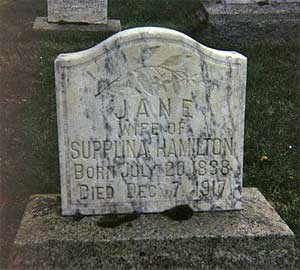

-- S. Hamilton.Every June some of Supplina's descendants still have our annual 'Hamilton Picnic', now in Spokane at Norman and Ellie Hamilton's farm (in their barn). This family tradition is at least 115 years old and was started by Supplina and Jane on the family farm near St. John. Supplina would clear out room in the barn after harvest and have extended family and friends in. It was also a common practice for him to turn the barn into the location for a mini 'Camp Meeting' and have a couple days of 'preaching.'Glen Hamilton has prepared (2014) an outline of Supplina Hamilton's life. Supplina ended his earthly sojourn early in 1905. His headstone has an adapted Scripture:"I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept the faith."

Jane lived another twelve years. They are both buried in the St. John Cemetery.

|

Even in death, the preacher signed his name as S. Hamilton. But Jane had the last word, so the world knows his given name. |

Main Pioneer Menu | Profiles Index | Search Engine